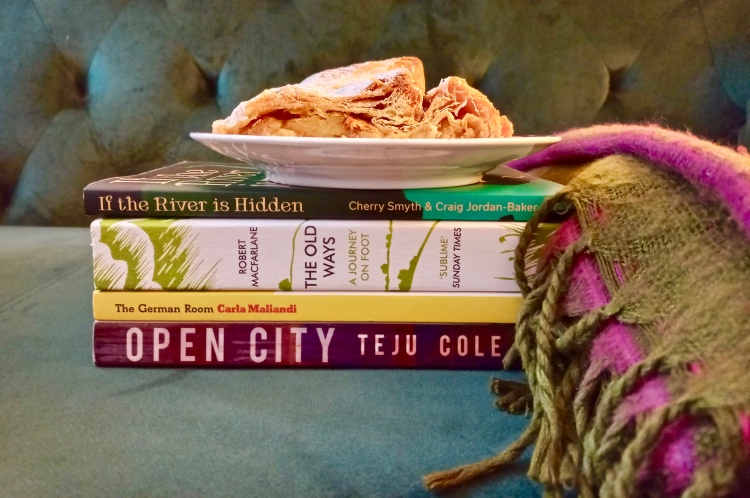

A review of Open City by Teju Cole

In Teju Cole’s Open City, a young man walks the streets of New York. Julius is a psychiatrist, born and raised in Nigeria, and later educated in the USA; following the death of his father and the return of his German mother to the country of her birth, he has become all but estranged from a family that was never quite functional in the first place. Julius’s rambles, which take place mostly at night and in the evening, are a quest to quiet his restless mind while getting to know his adopted city better, but also, it increasingly seems, an attempt to become better acquainted with himself.

As someone who loves wandering cities both familiar and foreign, I found Open City a joy to read. In Cole’s lyrical prose, the urban space – New York in particular, but also Brussels, where Julius spends a period of weeks over Christmas and New Year – becomes a character in its own right, in many ways more vivid than the narrator’s friends and family, even than Julius himself. Cole takes us down bustling thoroughfares and solemn backstreets, across parks and bridges, into shops and internet cafes, and reveals locations normally hidden to us: a refugee detention centre, an ageing professor’s apartment. Nowhere, it seems, is off limits, yet to read this novel is also to have the disconcerting sense of looking at the city through smoked glass. It is there, incredibly close yet somehow murky, requiring us constantly to tilt our heads in order to see better, visibly near yet physically out of reach.

Nowhere is this unsettling juxtaposition written better than in a brief passage around a third of the way into the novel, in which Julius happens upon a street festooned with flyers left over from a demonstration. Further down the road he can see an altercation taking place, yet distance means that both situations present themselves to him as ‘a silent commotion’, one of the thousands of small ruptures that make up daily life in a city and which have a fleeting yet profound impact on his own existence. In this passage, as in many others, Cole’s observations and framing are exquisite, his precise yet poetic language able to convey that hard-to-capture sense of being at one with a city while also disconnected from it. As a young Black man from another country, Julius’s narrative is also one of othering and belonging in the USA, a theme that begins as an undercurrent but swells powerfully over the course of the novel, and which is equally, if not more, urgent now as it was when Open City was first published a decade ago. This particular thread reaches its crescendo, perhaps, in a scene in which Julius is mugged by two men with whom he has just exchanged eye contact; further evidence that few things in the city are what they seem at first glance.

Though negative in its outcome, that encounter is one of a string of human interactions that will prove essential to our understanding of both narrative and narrator. Many have something oblique about them as they happen, yet in retrospect they function as small turning points in this light-on-plot novel, the street corners that provide Open City with its structure. There are the visits Julius pays to his former professor of literature, a late-night phone call with his ex-girlfriend, Nadège, a long conversation with the woman he finds himself sitting next to on a transatlantic flight, the philosophical musings of a new acquaintance in Brussels, a city quite different to New York yet pervaded also by ‘a palpable psychological pressure’. There are recollections of the past – his childhood, his early days in America, memories of a war that was never his passed down from his grandmother – and also, shockingly, a conversation with a former classmate’s sister that turns everything we think we know about our narrator on its head. Like all other events in the novel, Cole presents this particular moment without breaking the mesmerising flow of his prose, yet, looking back, it seems to be the ‘silent commotion’ at its heart, a scene that brings together memory, story and psychology to question how well we can ever know even ourselves.

The title of the novel can be read as both command and description, yet Open City is just as much about being closed as open. At an exhibition (setting for yet another opaque encounter with a stranger) Julius muses on photography as ‘an uncanny art like no other’, capable of capturing what may seem to us to be the truth, yet by definition only ever able to show one brief moment at a time. Taken out of context, photographs – individual moments – can be revelatory but also a means of telling a very specific story; Cole’s novel, too, can be read as a series of photos, snapshots of one life and the countless others with which it intersects on a daily basis. And this, indeed, is the great magic of the city: that it can be told from millions of similar yet entirely different perspectives. The one to which we have access here seems at first to want to give us the whole, but in the end only reveals a very small part of the picture.

‘New York City worked its way into my life at walking pace,’ declares Julius on the novel’s opening page, and it is at walking pace that Open City unfurls itself for us. Written in clipped, unsentimental tones that occasionally give way to a gorgeous lyricism or our narrator’s propensity for grand statements – ‘how petty seemed to me the human condition … this endless being tossed about like a cloud’ – this is a novel that marches to its own beat, a work of fiction that is both meditation and modern fable, the flâneur novel given a psychological twist. Cole ends Open City just as abruptly as he begins it (a novelist who makes the bold move of choosing ‘And’ as his opening word is to be admired), and for all that I had become unsettled by the company of Julius, I found myself briefly crushed that it was over. His life and all the lives of his New York were continuing elsewhere, silently, in a place to which I was no longer granted access. For a glorious moment, the city had come alive on the page. And then, just as swiftly, it was gone.

Open City by Teju Cole is published in the UK by Faber and in the USA by Random House.