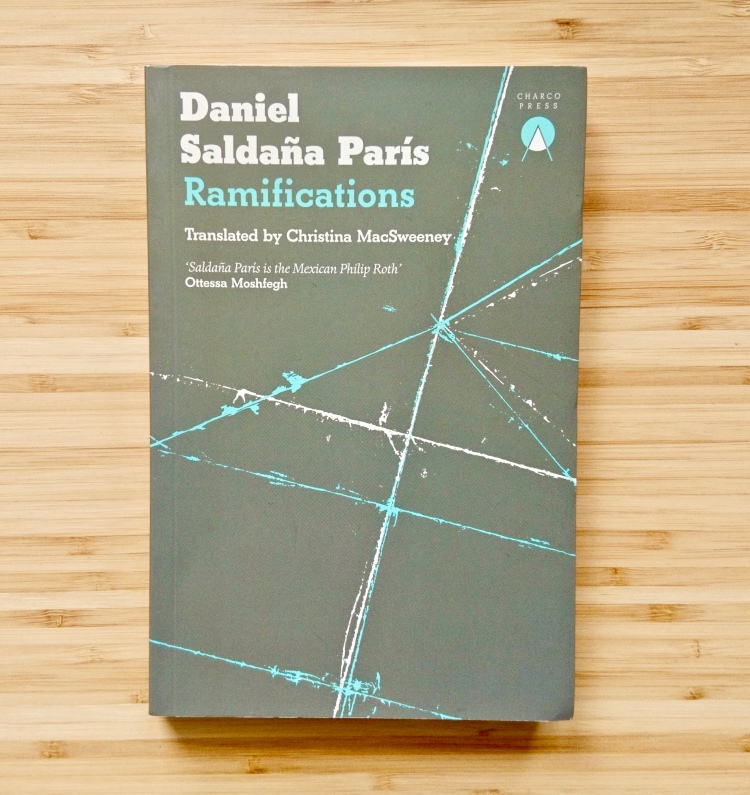

A review of Ramifications by Daniel Saldaña París, translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney

It was always going to be difficult to read fiction after Hurricane Season. Fortunately for me, there was Ramifications, another cracker from Latin American specialists Charco Press. Daniel Saldaña París’s second novel, vividly translated by Christina MacSweeney, offered me a return to Mexico that is sharp and structured, concealing beneath its apparently smooth surface a story rich in nuance and broad in scope, with some of the best characterisation I’ve had the pleasure of reading recently. Incisive, moving and gently absurd, Ramifications had me hooked from the very first sentence and through a process of gradual subversion left me feeling chilled to the core.

One Tuesday lunchtime, at ‘either the end of July or the beginning of August’ 1994, Teresa, our narrator’s mother, walks out on her two children. She bids them farewell as if she were simply running an errand, but instead of later returning to her family disappears to Chiapas to join the Zapatista uprising. At the time, our narrator and his older sister, Mariana, are simply informed by their father that their mother has ‘gone away’. And so concludes the single day that will inform the entirety of the story, leading our narrator to enter adulthood far too early and then, in turn, to withdraw from life, confining himself entirely to his bed where he pens the memories that become this novel. Unable to do anything but comb painstakingly through the past, at the age of thirty-two he continues to live largely in the world of ‘half-baked fantasy’ that was his childhood, desperately seeking a way to write himself back into existence, or – as we soon come to suspect – to erase himself altogether.

Much of the skill that lies in this novel is in Saldaña París’s extraordinary ability to give his narrator two voices simultaneously: that of the child and that of the adult. Though we are continually aware that he is looking back on his childhood – events are related in the past tense, with an almost clinical precision and gentle tone of mockery informed by an adult view of the world – the deeper we are drawn into the past, the more pronounced the child’s voice becomes. An outsider, the reader, is able to see both figures at once: the ten-year-old boy, sensitive and intelligent, traumatised by his mother’s unexplained disappearance and neglected by his emotionally absent father, but still able to view the world around him with something akin to awe; and, chillingly, the isolated, obsessive adult he will become. With his fears, foibles and strangely logical explanations for how the world works, the child’s voice is both superbly captured and disarming, offering brief glimpses into a universally recognisable world and indicating how our past selves inform our present incarnations more than we might like to believe.

As a coping strategy for the trauma bequeathed by his mother’s desertion, our narrator creates a fiction: Teresa has gone camping in Chiapas. This tendency to tell himself stories in order to explain a distressing event gradually seeps into the entire novel, colouring even the reader’s perception of the narrative and leaving us with the unsettling sense that our apparently meticulous, self-critical narrator may not be so reliable after all. As the novel slowly slides into chaos – egged on by Rat, a local delinquent with whom Mariana has struck up an undefined relationship, our narrator travels across Mexico City and boards a bus that will take him halfway to Chiapas, a journey that will see him further traumatised at a military checkpoint and eventually rescued and returned to his father by a woman who believes she is doing the right thing – we cannot be sure what is fact and what is fiction, or what belongs to the fickle in-betweenness of memory. As our narrator writes and rewrites his personal history, desperately seeking to uncover the truth, he succeeds only in muddying the waters – or, to turn to origami, one of the main metaphors in the book, in creasing the paper to such an extreme that it is no longer possible to smooth it.

Origami, with which our young narrator is infatuated, is a precise art form, one that requires considerable control and patience. These are two traits that can certainly be attributed to Saldaña París, whose ability to shape his narrative and thus steer the reader in exactly the direction he wants us to take is deserving of great admiration. While the novel appears to be folding ever in on itself as scraps of the past are worried again and again, by the time we have reached the startling conclusion – an unexpected twist that is as sinister as it is exhilarating to read – we appear instead by our narrator’s enchantingly named process of ‘reverse origami’ to have unfolded a bigger picture, one that offers an unusual, somewhat alarming portrait of patriarchy, family, emotional abuse, and the quiet traumas and unspoken violence woven throughout the social fabric of Mexico.

Ramifications also offers an unexpected and deeply moving insight into the fragility of the human mind, which though capable of folding itself into infinite permutations is not without its limits. It is here that the novel is at its most moving, and this theme – underlined by the carefully crafted structure that reflects it – is perhaps the most universal and important of all. Musing on his favourite subject as a boy, our narrator imagines ‘a Japanese monk, incarcerated in some pagoda . . . with only a sheet of paper, which he had to fold and unfold with infinite care, aware that if he tore it, his own sanity would be rent in two’. The comparison we can’t help but draw with his adult self is striking.

For all it engages with big themes, Ramifications is a delightful novel to read. In character-led fiction such as this, voice is everything, and Christina MacSweeney has done the world of literature a marvellous service in translating this particular voice into English. Lively and sharp-witted, it is almost impossible not to engage with, yet her chosen language allows plenty of room for melancholy, a haunting note that deeply unnerves the reader even as some of the more recognisable comedies of childhood entertain us. Imbued by the same ‘sense of absurdity, gratuitousness, and imminent disaster’ that plagues our narrator’s childhood, Ramifications is an intelligent, memorable novel by one of Mexico’s leading contemporary authors, an inspired examination of what the human mind can do to fiction – and what fiction, if we let it, can do to us.

Fantastic review, this sounds like such a captivating read. I’m always drawn to books that blur the line between fact and fiction, and the dual voice of the narrator at different ages sounds intriguing; I may have to pick this one up!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you very much! I really hope you get to give it a go. Charco Press tends to have such memorable narrative voices – just one of the reasons I’m always recommending them.

LikeLiked by 2 people